Arts and Crafts Mania

Published April 30th 1989 by the Chicago Tribune

Last December a telephone bidder bought an oak-and-wrought-iron sideboard created by cabinetmaker Gustav Stickley for the interior of Stickley`s home in Syracuse, N.Y., just after the turn of the century.

The bidder for the piece (pictured at the top of the page) was Barbra Streisand, the price was $363,000, and the result was a proven savvy collector putting her imprimatur on a hot collecting trend: Arts and Crafts.

”Barbra Streisand for a long time has gotten caught up with things that have become very popular-Art Nouveau, Art Deco and now Arts and Crafts,” said Don Treadway, an auctioneer and Cincinnati gallery owner. Treadway will be conducting a sale, ”Arts and Crafts in Chicago IV,” in association with John Toomey, owner of the North Boulevard Antique Center in Oak Park, next Sunday; a preview runs all this week at the shop, 818 North Blvd.

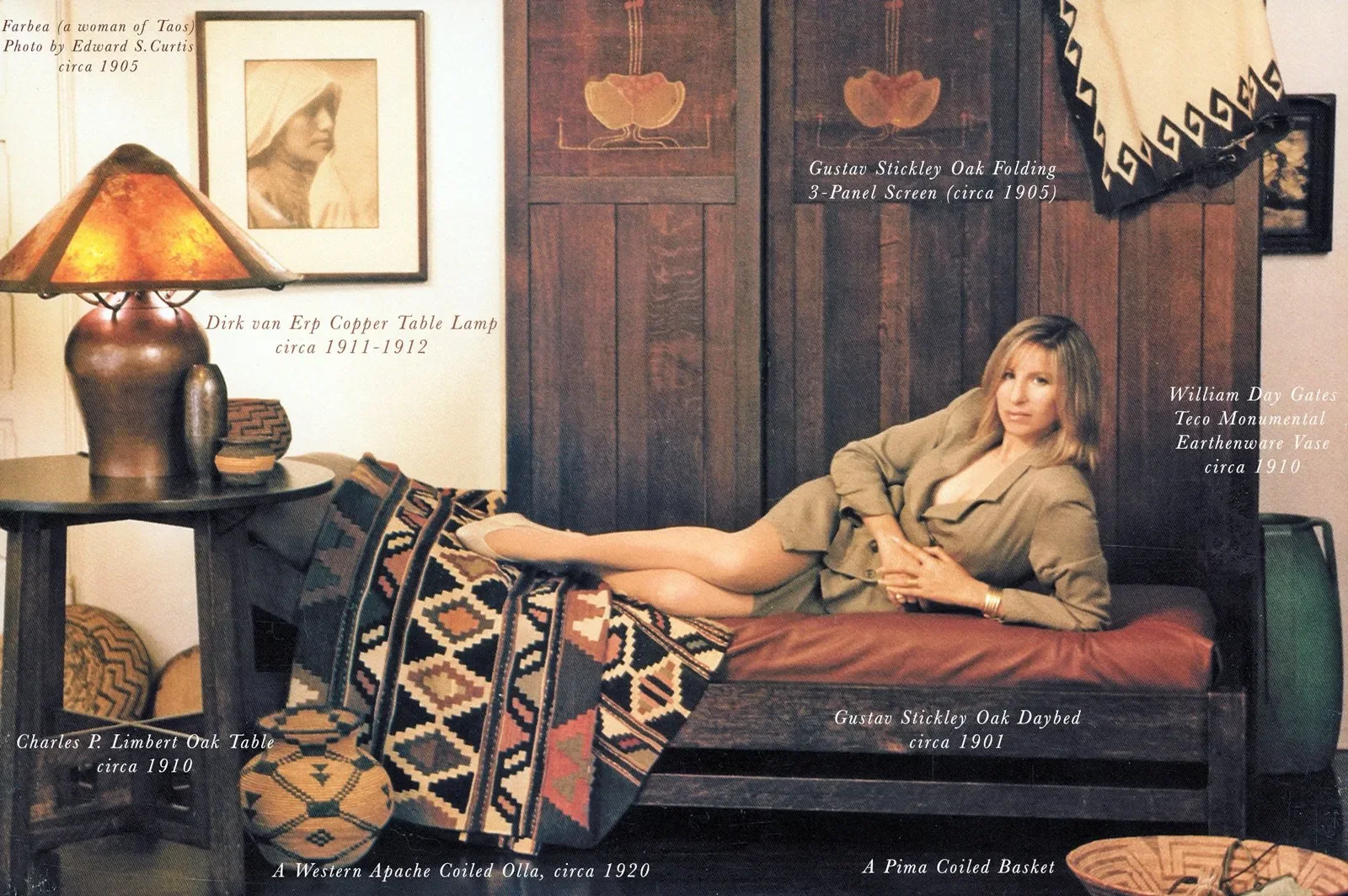

Barbra Streisand album cover of her 1989 album “A Collection: Greatest Hits and More (1989)” with notated objects from her personal collection.

”It is gaining momentum,” Toomey said. ”There are more collectors than ever before-more on the East Coast and West Coast but certainly a good core in Chicago. Celebrities add to the fever that runs up some of the price and some of the excitement.”

Streisand`s purchase price was a record for a single piece of Arts and Crafts furniture, according to Nancy McClelland, vice president in charge of 19th and 20th Century decorative arts at Christie`s auction house in New York. Richard Gere, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Jack Nicholson, movie producer Joel Silver (”Die Hard”) and Thomas Monaghan, the Domino`s Pizza tycoon and Frank Lloyd Wright collector, also are reported to be collecting Arts and Crafts, according to Toomey and Treadway.

”Stories on their homes in Architectural Digest, and the publicity on the prices they have paid, certainly have helped a lot to generate public interest,” said Marilee Meyer, head of the Arts and Crafts department at Skinner`s, a Boston auction house.

”But the bottom line is, it is good furniture design,” she said. ”It is here to stay. It is a very important movement.”

What is this stuff that is so attractive and adaptable to the lifestyles of the rich and famous?

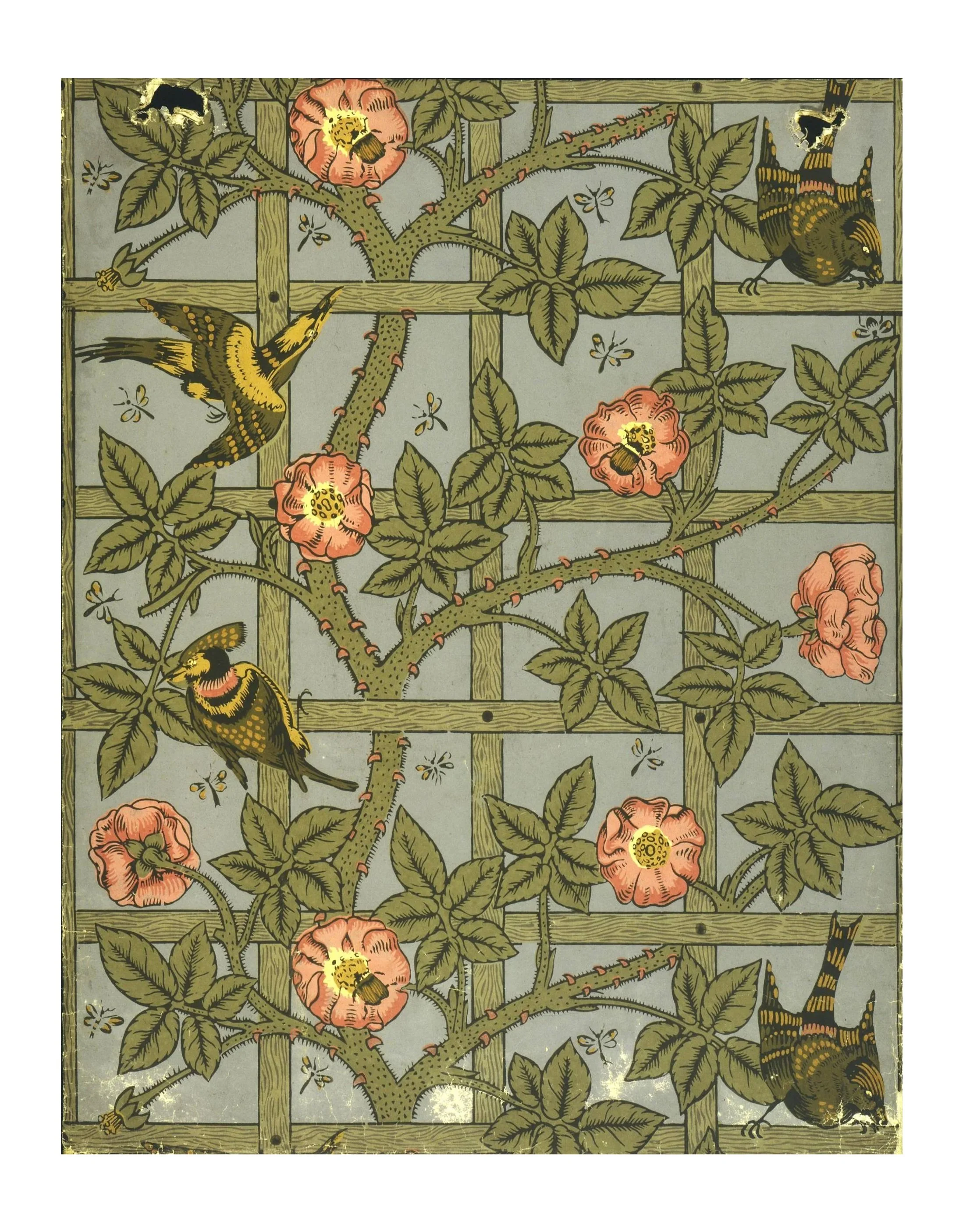

According to McClelland, ”The Arts and Crafts movement actually started in England as a protest against the Industrial Revolution. A lot of people like William Morris and John Ruskin deplored the bad design that people had to live with in their homes. (Morris was the leader of the English Arts and Crafts movement, and Ruskin was an English critic and essayist.)

Trellis wallpaper, designed by William Morris and Phillip Webb, printed by Jeffrey & Co., 1862, England. Museum no. E.452-1919. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

”The movement had two goals: one, to restore integrity and pride in individual workmanship, and two, to promote the `uncluttered` look as a reflection of the love of craftsmanship and simplicity.

”The people behind it believed there was a correlation between family life and their environment. If you have a simple, comfortable living environment, where it is harmonious and livable, it becomes a sanctuary,” she said.

Arrival in America

Arts and Crafts came to North America around the turn of the 20th Century, according to Michael FitzSimmons, director of Struve Gallery, 309 W. Superior St., and one of the top experts in the genre.

”Basically the Arts and Crafts movement spanned a period of about 15 years in America, from about 1900 to 1915,” FitzSimmons said. ”Obviously there is some margin on either side. The creative cutoff was World War I.

”What was the period about? It was an attempt to redefine or restructure the world. Leading up to the year 1900 was the Victorian era. Basically it was a period marked by excessiveness in decoration, in behavior, in architecture, furniture. People were basically getting tired of it. The world was weary, weighted down by all this overexuberant heaviness. People were looking forward eagerly to the change of the century because it gave them a logical breaking point.

”It was a new millennium. The avant-garde thinkers, politicians, scientists, anyone who had any kind of ability to shape the world, looked forward very eagerly to this clean slate. The whole world was being redesigned; so you needed everything new to conform to this exciting new idea. ”Basically what these designers did was they looked at the variety of discoveries and theories put forth at this time. They wanted to develop a total picture, believing that there is one unifying concept or principle that was at the base of everything in the universe.

”They didn`t know what that principle was, but they felt if they could pare away the excess from everything, they could discover this universal principle or at least get close to it and in so doing better their life, better their world. A big catchword back then was simplicity. But it did not mean `simple` because many of these things were sophisticated. The best definition of simplicity, as they knew it then, was `ordered.`

”And so you had an architect like Frank Lloyd Wright espousing his kind of architecture, simple, ordered and rational. His notion of organic architecture doesn`t mean it looks like plants. It meant rational and ordered.”

And in the forefront in America was Gustav Stickley.

Furniture for the times

”Stickley was one of the people who were great reformers and proselytizers who seized upon the tenor of the time and turned it into furniture,” FitzSimmons said. ”Up until this time, the notion that everything in your interior would harmonize not only among itself but also with the building was not even thought of.”

”His production furniture was the best being made,” McClelland said.

”He certainly was looking to England. He was an enormous admirer of William Morris. His first issue of Craftsman magazine (a decorative-arts magazine he began in 1901) was devoted to Morris.”

Gustav Stickley (middle) in his Syracuse NY factory, circa 1904, where they hand formed hardware and metal wares.

Born in Osceola, Wis., and trained by his father as a stonemason, Stickley as a young man found himself making chairs for an uncle in Pennsylvania. Introduced to the writings of Ruskin, he began thinking in terms that later made him one of the leading exponents of Arts and Crafts ideals in America.

In 1898 he took an extended trip to Europe, visiting leaders of design in England and on the Continent. From that point his work seldom had any historical reference; he designed metalwork, fabric, lighting, rugs and wicker as well as furniture.

”If you look at (Stickley`s) furniture, there is very little transition between high Victorian and Arts and Crafts, which shows that it was a real attempt to make a break,” FitzSimmons said. ”You didn`t get sort-of-Victorian, sort-of-Arts-and-Crafts; there was no subspecies.”

Chicago was one of the most important centers of the movement and one of the major centers of furniture production in the period, according to all of the experts. A number of Chicago Arts and Crafts groups had workshops and sales rooms in the Fine Arts Building at 408 S. Michigan Ave., and exhibitions were held at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gustav Stickley 8 Leg Sideboard. All original finish and hardware.

”Marshall Field`s had the exclusive selling Gustav Stickley furniture in Chicago. By 1902 they opened a Craftsman Showroom. A lot of times (Fields) put its name on Stickley furniture,” FitzSimmons said.

The craftsmen of the time ”produced a lot of furniture,” Treadway said. ”They had their art line, and they had a mass-production line. They furnished schools, courtrooms, hospitals, all sorts of large institutions. You can still find some Mission furniture in schools and courtrooms. Some people still call it `school furniture.` ”

(Sometimes Arts and Crafts furniture is called ”Mission” furniture or ”Mission oak.” )

”No one`s ever been able to figure that out,”

FitzSimmons said. ”It is believed it was coined because it was a mission to change the world, or it could have derived from a similarity between these designers and the furniture from the California Spanish missions, which by necessity was simple.”)

Interest renewed

The current renaissance of interest began in 1972, FitzSimmons believes, when there was an exhibition at Princeton called ”Arts and Crafts in America.”

”I think that brought for the first time to a great number of people what this furniture looked like.

”There are great, great pieces by designers other than Gustav Stickley that are easily affordable,” he said. ”A lot of attention goes to Gustav. That`s where the highest prices are being realized.”

But the experts say that is deserved. Stickley ”is unique in American design,” according to Toomey.

”Stickley used a combination of shortcuts with your factory machine, with the final touches handmade,” Meyer said. ”That`s what makes it American. Now you had democratic design. It was accessible to everybody.”

”Stickley,” Toomey said, ”has always had a following and he always will; whether it stays as hot as it is now, no one can say. There will be a lot of people who will lose interest at the lower level. But your best-designed pieces are pretty classical. That`s the appeal.

”It really is an American style. It`s very applicable to today. People are trying to get away from all the aggression out there. You go home, your home is your castle, you fill it with beautiful things. The stuff is plain but not simple; it is well-constructed design. A lot of people with awfully good eyes are attracted to it. And there`s a crossover into the art market right now.”

A modern look

”It seems to invoke in people a great sense of comfort and a great sense of ease, and it also has the unmistakable look of modern, which to our late 20th Century eyes is appealing as well,” FitzSimmons said. ”It is kind of like getting the best of everything. You get history and you get the fabulously rich variety of things.”

Collectors seek specific criteria in acquiring pieces, Toomey said. ”The design has to be rare, early; the finish has to be original (because the grain of the wood was made to be so expressive), and the piece should be signed. If it meets all those criteria, it is an important piece,” Toomey said. ”The price is pretty far up there for the early, original-finish piece.

”But a lot of late-period Gustav Stickley pieces-Stickley Bros., L.&J.G. Stickley (five of his brothers were making furniture) and Charles Limbert, a Grand Rapids, Mich., cabinetmaker-is still very affordable. You can still buy a Stickley Bros. Morris chair for $1,000 to $2,000. A good clean original finish by Gustav Stickley will cost $5,000. His early stuff is the rarest.”

But, Meyer said, you don`t have to be rich and famous to enjoy Arts and Crafts.

”First, Arts and Crafts is an area that is still affordable. There are a lot of bookcases and sideboards out there, actual, pure, signed Stickley pieces,” she said.

”What you read about are rare, unusual Stickley lines. You have your yuppies . . . collecting something that was not (created) in their lifetime. Their parents and grandparents remember it. These young people are restoring houses of this period and doing it authentically. Arts and Crafts is timeless design.” –