Craft, Community, and the Quiet Rebellion: The Guilds and Labor Roots of the Arts and Crafts Movement

When most people think of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they imagine clean lines, sturdy oak furniture, and hand-hammered copper. But behind the physical beauty of these objects lies something deeper: a bold social philosophy rooted in labor, dignity, and the value of human work. The original leaders of the movement—including William Morris in England and Gustav Stickley in America—weren’t just designers. They were reformers. And they believed that how something was made mattered just as much as the final form.

Richness does not entail luxury no simplicity cheapness - Gustav Stickley

A Movement Born from the Factory Age

In the mid-19th century, Britain was in the throes of the Industrial Revolution. Factory towns grew overnight, and workers became cogs in machines, producing cheap goods in harsh conditions. Artists, writers, and craftspeople began to ask: What have we lost in the name of progress?

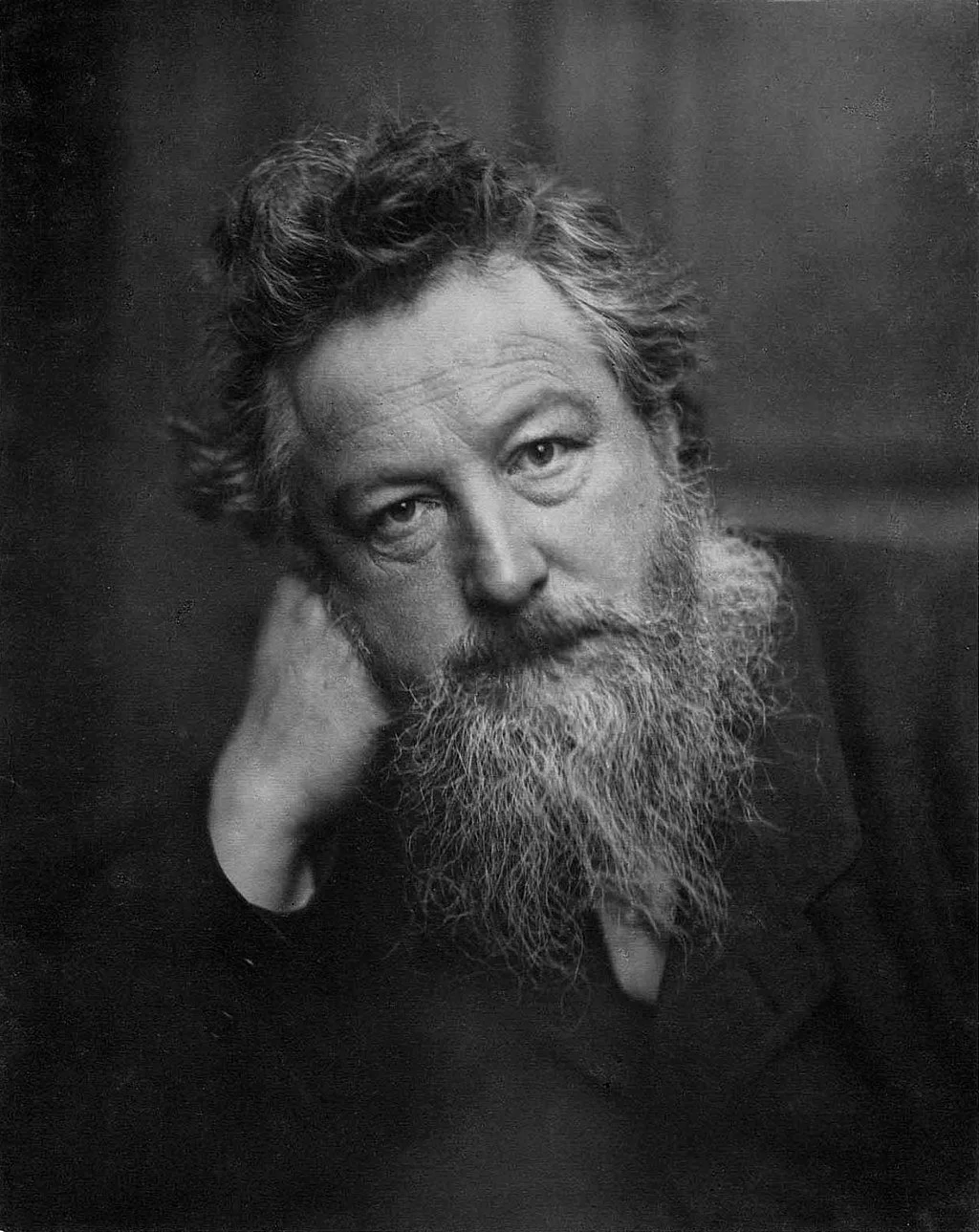

William Morris, a poet, printer, and designer, became the face of the Arts and Crafts Movement in England. He believed industrial production degraded not just the product but the worker. In his words, “the true secret of happiness lies in taking a genuine interest in all the details of daily life.” That included the act of making—by hand, with care, and with pride.

To counter the dehumanizing effects of mass production, Morris established The Firm (later Morris & Co.) in 1861. It was a collective of artists and craftsmen who produced stained glass, textiles, wallpaper, and furniture—items meant to enrich everyday life. But this wasn’t just a business. It was a guild, an intentional community based on shared labor, mutual respect, and fair wages. For Morris, craft was a form of social justice.

The American Extension: Gustav Stickley’s Utopia

Across the Atlantic, Gustav Stickley absorbed Morris’s ideas and gave them an American spin. A furniture maker by trade, Stickley believed in honest materials, structural integrity, and the value of handwork. But he also believed in something rarer: that workers should be treated with dignity and that craft could elevate both the maker and the consumer.

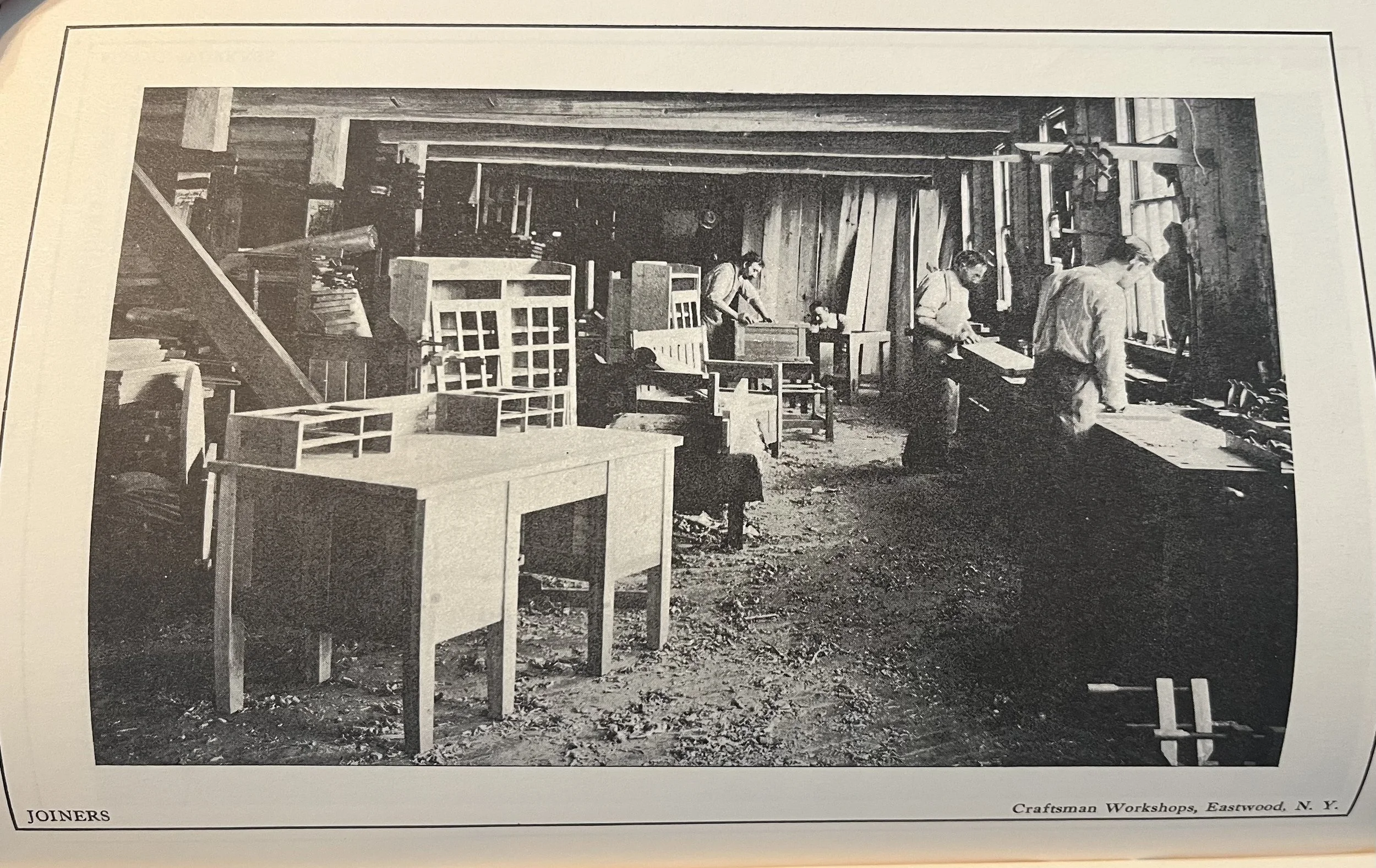

In 1901, Stickley founded the United Crafts (soon renamed Craftsman Workshops), an American answer to Morris’s guild. He employed woodworkers, metalworkers, upholsterers, and designers under one roof—not as anonymous laborers, but as part of a greater vision. His business model emphasized education, collaboration, and a living wage. He believed that dignified labor was art at a time when factories were exploiting labor, Stickley’s workshops were an act of rebellion.

“In a real and important sense, Stickley liberated the artisan - the craftsperson - and elevated him or her to the level of artist” (The Complex Fait of Gustav Stickley by Barry Sanders)

Gustav’s publication, The Craftsman, wasn't just a sales tool—it was a philosophical manifesto. He wrote about the value of simple living, the moral responsibility of design and how it could elevate humanity, and the possibility of a more harmonious world through beautiful, well-made things.

“What is Wrought in The Craftsman Workshops” The Craftsman Publication 1904.

Beyond Business: A Way of Life

Both Morris and Stickley understood that the guild system wasn't merely about how objects were produced. It was about building a society where art, labor, and daily life were integrated. Where people weren’t alienated from the work of their hands. Where a cabinetmaker had as much cultural value as a poet.

These early Arts and Crafts guilds were part of a broader labor movement. They sought to restore agency to the worker, emphasizing skill over speed, integrity over profit. Many other figures followed in their footsteps—Charles Robert Ashbee and the Guild of Handicraft in London; Elbert Hubbard and the Roycrofters in East Aurora, New York. Each of these communities tried to align moral, artistic, and economic values in a world increasingly shaped by machines.

“What is Wrought in The Craftsman Workshops” The Craftsman Publication 1904.

Why It Still Matters

Today, the ideals of the Arts and Crafts guilds feel more relevant than ever. As we confront fast fashion, disposable furniture, and burnout culture, the movement reminds us that there is another way. A slower, more sustainable way. One where quality, community, and craftsmanship matter.

At Euro Classics Antiques, we see ourselves as part of that tradition. Every time we restore a Stickley chair or a Limbert sideboard, we’re not just preserving a piece of furniture—we’re honoring a legacy. A legacy of makers who believed their work had meaning beyond profit. A legacy of guilds that dared to dream of a better world through better work.

This is the quiet rebellion we invite you to join.